Chapter One — Sacred Ground

“The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know.”—Harry Truman

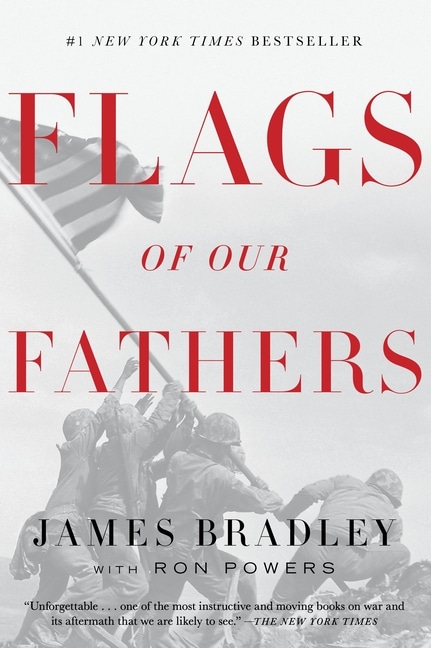

In the spring of 1998, six boys called to me from half a century ago on a distant mountain and I went there. For a few days I set aside my comfortable life—my business concerns, my life in Rye, New York—and made a pilgrimage to the other side of the world, to a primitive flyspeck island in the Pacific. There, waiting for me, was the mountain the boys had climbed in the midst of a terrible battle half a century earlier. One of them was my father. The mountain was called Suribachi; the island, Iwo Jima.

The fate of the late-twentieth and twenty-first centuries was forged in blood on that island and others like it. The combatants, on either side, were kids—kids who had mostly come of age in cultures that resembled those of the nineteenth century. My young father and his five comrades were typical of these kids. Tired, scared, thirsty, brave; tiny integers in the vast confusion of war-making, trying to do their duty, trying to survive.

But something unusual happened to these six: History turned all its focus, for 1/400th of a second, on them. It froze them in an elegant instant of battle: froze them in a camera lens as they hoisted an American flag on a makeshift pole. Their collective image, blurred and indistinct yet unforgettable, became the most recognized, the most reproduced, in the history of photography. It gave them a kind of immortality—a faceless immortality. The flagraising on Iwo Jima became a symbol of the island, the mountain, the battle; of World War II; of the highest ideals of the nation, of valor incarnate. It became everything except the salvation of the boys who formed it.

Chapter opener: James Bradley on the beach of Iwo Jima, April 1998. For these six, history had a different set of agendas. Three were killed in action in the continuing battle. Of the three survivors, two were overtaken and eventually destroyed—dead of drink and heartbreak. Only one of them managed to live in peace into an advanced age. He achieved this peace by willing the past into a cave of silence.

My father, John Henry Bradley, returned home to small-town Wisconsin after the war. He shoved the mementos of his immortality into a few cardboard boxes and hid these in a closet. He married his third-grade sweetheart. He opened a funeral home; fathered eight children; joined the PTA, the Lions, the Elks; and shut out any conversation on the topic of raising the flag on Iwo Jima.

When he died in January 1994, in the town of his birth, he might have believed he was taking the unwanted story of his part in the flagraising with him to the grave, where he apparently felt it belonged. He had trained us, as children, to deflect the phone-call requests for media interviews that never diminished over the years. We were to tell the caller that our father was on a fishing trip. But John Bradley never fished. No copy of the famous photograph hung in our house.

When we did manage to extract from him a remark about the incident, his responses were short and simple and he quickly changed the subject. And this is how we Bradley children grew up: happily enough, deeply connected to our peaceful, tree-shaded town, but always with a sense of an unsolved mystery somewhere at the edges of the picture. We sensed that the outside world knew something important about him that we would never know.

For him, it was a dead issue; a boring topic. But not for the rest of us. Me, especially.

For me, a middle child among the eight, the mystery was tantalizing. I knew from an early age that my father had been some sort of hero. My third-grade schoolteacher said so; everybody said so. I hungered to know the heroic part of my dad. But try as I might I could never get him to tell me about it.

“The real heroes of Iwo Jima,” he said once, coming as close as he ever would, “are the guys who didn’t come back.”

John Bradley might have succeeded in taking his story to his grave had we not stumbled upon the cardboard boxes a few days after his death.

My mother and brothers Mark and Patrick were searching for my father’s will in the apartment he had maintained as his private office. In a dark closet they discovered three heavy cardboard boxes, old but in good shape, stacked on top of each other.

In those boxes my father had saved the many photos and documents that came his way as a flagraiser. All of us were surprised that he had saved anything at all.

Later I rummaged through the boxes. One letter caught my eye. The cancellation indicated it was mailed from Iwo Jima on February 26, 1945. A letter written by my father to his folks just three days after the flagraising.

The carefree, reassuring style of his sentences offers no hint of the hell he had just been through. He managed to sound as though he were on a rugged but enjoyable Boy Scout hike: “I’d give my left arm for a good shower and a clean shave, I have a 6 day beard. Haven’t had any soap or water since I hit the beach. I never knew I could go without food, water or sleep for three days but I know now, it can be done.”

And then, almost as an aside, he wrote: “You know all about our battle out here. I was with the victorious [Easy Company] who reached the top of Mt. Suribachi first. I had a little to do with raising the American flag and it was the happiest moment of my life.”

The “happiest moment” of his life! What a shock to read that. I wept as I realized the flagraising had been a happy moment for him as a twenty-one-year-old. What happened in the intervening years to cause his silence?

Reading my father’s letter made the flagraising photo somehow come alive in my imagination. Over the next few weeks I found myself staring at the photo on my office wall, daydreaming. Who were those boys with their hands on that pole? I wondered. Were they like my father? Had they known one another before that moment or were they strangers, united by a common duty? Did they joke with one another? Did they have nicknames? Was the flagraising “the happiest moment” of each of their lives?

The quest to answer those questions consumed four years. At its outset I could not have told you if there were five or six flagraisers in that photograph. Certainly I did not know the names of the three who died during the battle.

By its conclusion, I knew each of them like I know my brothers, like I know my high-school chums. And I had grown to love them.

What I discovered on that quest forms the content of this book. The quest ended, symbolically, with my own pilgrimage to Iwo Jima.

Accompanied by my seventy-four-year-old mother, three of my brothers, and many military men and women, I ascended the 550-foot volcanic crater that was Mount Suribachi. My twenty-one-year-old father had made the climb on foot carrying bandages and medical supplies; our party was whisked up in Marine Corps vans. I stood at its summit in a whipping wind that helped dry my tears. This was exactly where that American flag was raised on a February afternoon fifty-three years before. The wind had whipped on that day as well. It had straightened the rippling fabric of that flag by its force.

Not many Americans make it to Iwo Jima these days. It is a shrine of World War II, but it is not an American shrine. A closed Japanese naval base, it is inaccessible to civilians of all nationalities except for rare government-sanctioned visits.

It was the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Charles Krulak, who made our trip possible. He offered to fly us from Okinawa to Iwo Jima on his own plane. My mother, Betty, and three of my brothers—Steve, then forty-eight, Mark, forty-seven, and Joe, thirty-seven—made the trip with me. (I was forty-four.) Not everyone in the clan could. Brothers Patrick and Tom stayed at home, as did sisters Kathy and Barbara.

Departing Okinawa for the island on a rainswept Tuesday aboard General Krulak’s plane, we were warned that we could expect similar weather at our destination. But two hours later, as we began our descent to Iwo Jima, the clouds suddenly parted and Suribachi loomed ahead of us bathed in bright sun, a ghost-mountain from the past thrust suddenly into our vision.

As the plane banked its wings, circling the island twice to allow us close-up photographs of Suribachi and the outlying terrain, the commandant began speaking of Iwo Jima, in a low voice, as being “holy land” and “sacred ground.” “It’s holy ground to both us and the Japanese,” he added thoughtfully at one point.

A red carpet was rolled out and waiting for my mother as she stepped off the plane, the first of us to exit. A cadre of Japanese soldiers stood at strict attention along one side; U.S. Marines flanked the other.

General Krulak presented my mother to the Japanese commandant on the island, Commander Kochi. We were, indeed, the guests of the commander and his small garrison. American forces might have captured Iwo Jima in the early weeks of 1945, but today the island is a part of Japan’s sovereign state.

Unlike in 1945, we had landed this time with their permission.

A visitor is inevitably struck by the impression that Iwo Jima is a very small place to have hosted such a big battle. The island is a trivial scab barely cresting the infinite Pacific, its eight square miles only about a third the mass of Manhattan Island. One hundred thousand men battled one another here for over a month, making this one of the most intense and closely fought battles of any war.

Eighty thousand American boys fought aboveground, twenty thousand Japanese boys fought from below. They were hidden in a sophisticated tunnel system that crisscrossed the island; reinforced tunnels that had rendered the furiously firing Japanese all but invisible to the exposed attackers.

Sixteen miles of tunnels connecting fifteen hundred man-made caverns. Many surviving Marines never saw a live Japanese soldier on Iwo Jima. They were fighting an enemy they could not see.

We boarded Marine vans and drove to the “Hospital Cave,” an enormous underground hospital where Japanese surgeons had quietly operated on their wounded forty feet below advancing Marines. Hospital beds had been carved into the volcanic-rock walls.

We then entered a large cavern that had housed Japanese mortar men. On the cavern wall were markers that corresponded to the elevations of the sloping beaches. This allowed the Japanese to angle their mortar tubes so they could hit the invading Marines accurately. The beaches of Iwo Jima had been preregistered for Japanese fire. The hell the Marines walked through had been rehearsed for months.

We drove across the island to the old combat site where my father had been wounded two weeks after the flagraising. I noticed that the ground was hard, and rust-colored. I stooped down and picked up one of the shards of rock that littered the surface. Examining it up close, I realized that it was not a rock at all. It was a piece of shrapnel. This is what we had mistaken for natural terrain: fragments of exploded artillery shells. Half a century old, they still formed a kind of carpet here. My father carried some of that shrapnel in his leg and foot to his grave.

Then it was on to the invasion beaches, the sands of Iwo Jima. We walked across the beach closest to Mount Suribachi. The invading Marines had dubbed it “Green Beach” and it was across this killing field that young John Bradley, a Navy corpsman, raced under decimating fire.

Now I watched as my mother made her way across that same beach, sinking to her ankles in the soft volcanic sand with each step. “I don’t know how anyone survived!” she exclaimed. I watched her move carefully in the wind and sunlight: a small white-haired widow now, but a world ago a pretty little girl named Betty Van Gorp of Appleton, Wisconsin, who found herself in third-grade class with a new boy, a serious boy named John. My father walked Betty home from school every day for the stretch of the early 1930’s when he lived in Appleton, because her house was on his street. When he came home from World War II a decade and a half later, he married her.

Two hundred yards inland from where she now stood, on the third day of the assault, John Bradley saw an American boy fall in the distance. He raced through the mortar and machine-gun fire to the wounded Marine, administered plasma from a bottle strapped to a rifle he’d planted in the sand, and then dragged the boy to safety as bullets pinged off the rocks.

For his heroism he was awarded the Navy Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor.

John Bradley never confided the details of his valor to Betty. Our family did not learn of his Navy Cross until after he had died.

Now Steve took my mother’s arm and steadied her as she walked up the thick sand terraces. Mark stood at the water’s edge lost in thought, facing out to sea. Joe and I saw a blockhouse overlooking the beach and made our way to it.

The Japanese had installed more than 750 blockhouses and pillboxes around the island: little igloos of rounded concrete, reinforced with steel rods to make them virtually impervious even to artillery rounds. Many of their smashed white carcasses still stood, like skeletons of animals half a century dead, at intervals along the strand. The blockhouses were hideous remnants of the island defenders’ fanaticism in a cause they knew was lost. The soldiers assigned to them had the mission of killing as many invaders as possible before their own inevitable deaths.

Joe and I entered the squat cement structure. We could see that the machine-gun muzzle still protruding through its firing slit was bent–probably from overheating as it killed American boys. We squeezed our way inside. There were two small rooms, dark except for the brilliant light shining through the hole: one room for shooting, the other for supplies and concealment against the onslaught.

Hunched with my brother in the confining darkness, I tried to imagine the invasion from the viewpoint of a defending blockhouse occupant: He created terror with his unimpeded field of fire, but he must have been terrified himself; a trapped killer, he knew that he would die there—probably from the searing heat of a flamethrower thrust through the firing hole by a desperate young Marine who had managed to survive the machine-gun spray.

What must it have been like to crouch in that blockhouse and watch the American armada materialize offshore? How many days, how many hours did he have to live? Would he attain his assigned kill-ratio of ten enemies before he was slaughtered?

What must it have been like for an American boy to advance toward him? I thought of my own interactions with the Japanese when I was in my early twenties. I attended college in Tokyo and my choices were study or sushi.

But for too many on bloody Iwo there were no choices; it had been kill or be killed. But now it was time to ascend the mountain.

Standing where they raised the flag at the edge of the extinct volcanic crater, the wind whipping our hair, we could view the entire two-mile beach where the armada had discharged its boatloads of attacking Marines.

In February 1945 the Japanese could see it with equal clarity from the tunnels just beneath us. They waited patiently until the beach was chockablock with American boys. They had spent many months prepositioning their gun sights. When the time came, they simply opened fire, beginning one of the great military slaughters of all history.

An oddly out-of-place feeling now seized me: I was so glad to be up here!

The vista below us, despite the gory freight of its history, was invigorating. The sun and the wind seemed to bring all of us alive.

And then I realized that my high spirits were not so out of place at all. I was reliving something. I recalled the line from the letter my father wrote three days after the flagraising: “It was the happiest moment of my life.”

Yes, it had to be exhilarating to raise that flag. From Suribachi, you feel on top of the world, surrounded by ocean. But how had my father’s attitude shifted from that to “If only there hadn’t been a flag attached to that pole”?

As some twenty young Marines and older officers milled around us, we Bradleys began to take pictures of one another. We posed in various spots, including near the “X” that marks the spot of the actual raising. We had brought with us a plaque: shiny red, in the “mitten” shape of Wisconsin and made of Wisconsin ruby-red granite, the state stone. Part of our mission here was to embed this plaque in the rough rocky soil. Now my brother Mark scratched in that soil with a jackknife. He swept the last pebbles from the newly bared area and said, “OK, it should fit now.”

Joe gently placed the plaque in the dry soil. It read:

TO JOHN H. BRADLEY

FLAGRAISER FEB. 23, 1945

FROM HIS FAMILY

We stood up, dusted our hands, and gazed at our handiwork. The wind blew through our hair. The hot Pacific sun beat down on us. Our allotted time on the mountain was drawing short.

I trotted over to one of the Marine vans to retrieve a folder that I had carried with me from New York for this occasion. It contained notes and photographs: a few photographs of Bradleys, but mostly of the six young men. “Let’s do this now,” I called to my family and the Marines who accompanied us up the mountain as I motioned them over to the marble monument which stands atop the mountain.

When the Marines had gathered in front of the memorial, everyone was silent for a moment. The world was silent, except for the whipping wind.

And then I began to speak.

I spoke of the battle. It ground on over thirty-six days. It claimed 25,851 U.S. casualties, including nearly 7,000 dead. Most of the 22,000 defenders fought to their deaths.

It was America’s most heroic battle. More medals for valor were awarded for action on Iwo Jima than in any battle in the history of the United States. To put that into perspective: The Marines were awarded eighty-four Medals of Honor in World War II. Over four years, that was twenty-two a year, about two a month.

But in just one month of fighting on this island, they were awarded twenty-seven Medals of Honor: one third their accumulated total.

I spoke then of the famous flagraising photograph. I remarked that nearly everyone in the world recognizes it. But no one knows the boys.

I glanced toward the frieze on the monument, a rendering of the photo’s image.

I’d like to tell you, I said, a little about them now.

I pointed to the figure in the middle of the image. Solid, anchoring, with both hands clamped firmly on the rising pole.

Here is my father, I said.

He is the most identifiable of the six figures, the only one whose profile is visible. But for half a century he was almost completely silent about Iwo Jima. To his wife of forty-seven years he spoke about it only once, on their first date. It was not until after his death that we learned of the Navy Cross. In his quiet humility he kept that from us. Why was he so silent? I think the answer is summed up in his belief that the true heroes of Iwo Jima were the ones who didn’t come back.

(There were other reasons for my father’s silence, as I had learned in the course of my quest. But now was not the time to share them with these Marines.)

I pointed next to a figure on the far side of John Bradley, and mostly obscured by him. The handsome mill hand from New Hampshire. Rene Gagnon stood shoulder to shoulder with my dad in the photo, I said.

But in real life they took the opposite approach to fame. When everyone acclaimed Rene as a hero–his mother, the President, Time magazine, and audiences across the country—he believed them. He thought he would benefit from his celebrity. Like a moth, Rene was attracted to the flame of fame.

I gestured now to the figure on the far right of the image; toward the leaning, thrusting figure jamming the base of the pole into the hard Suribachi ground. His right knee is nearly level with his shoulder. His buttocks strain against his fatigues. The Texan.

Harlon Block, I said. A star football player who enlisted in the Marines with all the seniors on his high-school football team. Harlon died six days after they raised the flag. And then he was forgotten. Harlon’s back is to the camera and for almost two years this figure was misidentified. America believed it was another Marine, who also died on Iwo Jima.

But his mother, Belle, was convinced it was her boy. Nobody believed her, not her husband, her family, or her neighbors. And we would never have known it was Harlon if a certain stranger had not walked into the family cotton field in south Texas and told them that he had seen their son Harlon put that pole in the ground.

Next I pointed to the figure directly in back of my father. The Huck Finn of the group. The freckle-faced Kentuckian.

Here’s Franklin Sousley from Hilltop, Kentucky, I said. He was fatherless at the age of nine and sailed for the Pacific on his nineteenth birthday. Six months earlier, he had said good-bye to his friends on the porch of the Hilltop General Store. He said, “When I come back I’ll be a hero.”

Days after the flagraising, the folks back in Hilltop were celebrating their hero. But a few weeks after that, they were mourning him. I gazed at the frieze for a moment before I went on.

Look closely at Franklin’s hands, I asked the silent crowd in front of me. Do you see his right hand? Can you tell that the man in back of him has grasped Franklin’s right hand and is helping Franklin push the heavy pole?

The most boyish of the flagraisers, I said, is getting help from the most mature. Their veteran leader. The sergeant. Mike Strank. I pointed now to what could be seen of Mike.

Mike is on the far side of Franklin, I said. You can hardly see him. But his helping young Franklin was typical of him. He was respected as a great leader, a “Marine’s Marine.” To the boys that didn’t mean that Sergeant Mike was a rough, tough killer. It meant that Mike understood his boys and would try to protect their lives as they pursued their dangerous mission.

And Sergeant Mike did his best until the end. He was killed as he was drawing a diagram in the sand showing his boys the safest way to attack a position.

Finally I gestured to the figure at the far left of the image. The figure stretching upward, his fingertips not quite reaching the pole. The Pima Indian from Arizona.

Ira Hayes, I said. His hands couldn’t quite grasp the pole. Later, back in the United States, Ira was hailed as a hero but he didn’t see it that way.

“How can I feel like a hero,” he asked, “when I hit the beach with two hundred and fifty buddies and only twenty-seven of us walked off alive?”

Iwo Jima haunted Ira, and he tried to escape his memories in the bottle. He died ten years, almost to the day, after the photo was taken.

Six boys. They form a representative picture of America in 1945: a mill worker from New England; a Kentucky tobacco farmer; a Pennsylvania coal miner’s son; a Texan from the oil fields; a boy from Wisconsin’s dairy land, and an Arizona Indian.

Only two of them walked off this island. One was carried off with shrapnel embedded up and down his side. Three were buried here. And so they are also a representative picture of Iwo Jima. If you had taken a photo of any six boys atop Mount Suribachi that day, it would be the same: two-thirds casualties. Two out of every three of the boys who fought on this island of agony were killed or wounded.

When I was finished with my talk, I couldn’t look up at the faces in front of me. I sensed the strong emotion in the air. Quietly, I suggested that in honor of my dad, we all sing the only two songs John Bradley ever admitted to knowing: “Home on the Range” and “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.”

We sang. All of us, in the sun and whipping wind. I knew, without looking up, that everyone standing on this mountaintop with me—Marines young and old, women and men; my family—was weeping. Tears were streaming down my own face. Behind me, I could hear the hoarse sobs coming from my brother Joe. I hazarded one glance upward—at Sergeant Major Lewis Lee, the highest-ranking enlisted man in the Corps. Tanned, his sleeves rolled up over brawny forearms, muscular Sergeant Major Lee looked like a man who could eat a gun, never mind shoot one. Tears glistened on his chiseled face.

Holy land. Sacred ground.

And then it was over.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.